Serverless Web Scraping with AWS, Part I

January 31, 2021

How do I build an automated ETL pipeline from a simple web scraper? Over two posts, I document the resources I leverage to periodically extract solar irradiance and meteorological data from the Solar Energy Research Institute's (SRRL) online portal. This first post will focus on developing the ETL pipeline itself.

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) established the SRRL as a means to monitor solar resources on a continuous basis. Located in Golden, CO, the lab houses a Baseline Measurement System (BMS) that records a trove of irradiance data at a granularity of 1-minute intervals.

While the website contains some fairly user-friendly endpoints, download options aren't updated on a real-time basis, and the live views refresh periodically. Thus, I decided to construct an ETL pipeline to access it, just so I can do some EDA down the line. Textbook overkill.

Setting up a PostgreSQL Instance on RDS

Turns out there're better ways to store data than etching it into the walls of my rental home, so I set up a Postgres database on Amazon Web Services. It's a simple setup with 3 tables:

stations: currently just links extracted data to one measurement site: NREL Solar Radiation Research Laboratory (BMS). If we pull data from other sites in the future, this table will become more relevant.irradiance: tracks global, direct, and diffuse irradiance in W/m^2 using different instruments. There's even vertical-facing collectors logging data for each of the cardinal directions.meteorological: tracks hyper-local meteorological conditions, such as albedo, zenith / azimuth angles relative to the sun, temperature, and wind speed.

The Measurement and Instrumentation Data Center (MIDC) has

descriptions of metrics and the instruments

responsible for recording them. Check out ./query_history

in the repo to see the which fields I'm tracking.

Creating the Web Scraper

Now that we have a database to load into, we can focus on extracting and

transforming data using Python. We'll rely on the Scrapy framework

here to crawl and extract structured data from the target endpoints. Running

scrapy startproject nrel_scraper provides a simple architecture to develop on.

MIDC Spider

# ./nrel_scraper/spiders/midc_spider.py

import scrapy

from nrel_scraper.items import NrelScraperItem

class MidcSpider(scrapy.Spider):

name = "midc"

start_urls = [

'https://midcdmz.nrel.gov/apps/plot.pl?site=BMS&start=20200101&live=1&zenloc=222&amsloc=224&time=1&inst=15&inst=22&inst=41&inst=43&inst=45&inst=46&inst=47&inst=48&inst=49&inst=50&inst=51&inst=52&inst=53&inst=55&inst=62&inst=63&inst=74&inst=75&type=data&wrlevel=6&preset=0&first=3&math=0&second=-1&value=0.0&global=-1&direct=-1&diffuse=-1&user=0&axis=1',

'https://midcdmz.nrel.gov/apps/plot.pl?site=BMS&start=20200101&live=1&zenloc=222&amsloc=224&time=1&inst=130&inst=131&inst=132&inst=134&inst=135&inst=142&inst=143&inst=146&inst=147&inst=148&inst=149&inst=150&inst=151&inst=156&inst=157&inst=158&inst=159&inst=160&inst=161&inst=164&inst=172&inst=173&type=data&wrlevel=6&preset=0&first=3&math=0&second=-1&value=0.0&global=-1&direct=-1&diffuse=-1&user=0&axis=1'

]

# Associate url with corresponding postgres table in RDS instance

map_table = {k:v for k, v in zip(start_urls, ['irradiance', 'meteorological'])}

def parse(self, response):

data_text = response.xpath('//body/p/text()').get()

# Identify correct table to push parsed data to

push_to_table = self.map_table.get(response.request.url, None)

# Yield data

yield NrelScraperItem(data_text = data_text, table = push_to_table)

The actual spider itself has a fairly simple definition, with start_urls listing

the endpoints that Scrapy should crawl (irradiance and meteorological data,

respectively). Because the parse() method is Scrapy's default callback method

for each of the requests, it doesn't need to be called explicitly.

The custom return object NrelScraperItem is defined in items.py. It expects

to field the raw text data, and a string describing the relevant table to push to.

The former is literally ASCII text nested within a <body> tag, so is easily extracted.

In hindsight, using a simpler tool like BeautifulSoup

would be more than enough to service my needs. But soup is overrated. Fight me.

Item Pipeline

# ./nrel_scraper/pipelines.py

from itemadapter import ItemAdapter

from sqlalchemy import create_engine

from io import StringIO

import pandas as pd

import os

from dotenv import load_dotenv

load_dotenv()

class NrelScraperPipeline(object):

def open_spider(self, spider):

# Retrieve environment variables and keys

hostname = os.getenv('HOSTNAME')

username = os.getenv('USERNAME')

password = os.getenv('PASSWORD')

database = os.getenv('DATABASE')

# Create SQLAlchemy engine

self.engine = create_engine(f'postgresql://{username}:{password}@{hostname}:5432/{database}')

def close_spider(self, spider):

self.engine.dispose()

def process_item(self, item, spider):

# Read ASCII text data into pandas dataframe and process

df = pd.read_csv(StringIO(item['data_text']), sep=",")

# Clean dataframe

df['measurement_ts'] = pd.to_datetime(df['DATE (MM/DD/YYYY)'] + ' ' + df['MST']).dt.tz_localize('MST')

df.drop(['DATE (MM/DD/YYYY)', 'MST'], axis=1, inplace=True)

df['station_id'] = 1

df.columns = df.columns.str.lower()\

.str.replace("\(.*\)|\[.*\]", '', regex=True)\

.str.replace('li-200', 'li200')\

.str.strip().str.replace('-|\W+', '_', regex=True)

# Write to associated table in Postgres

df.to_sql(item['table'], self.engine, if_exists='append', index=False)

return f"====> Data processed to: {item['table']} table in {self.engine.url.database}"

The extracted return object NrelScaperItem must now be transformed and loaded

into our designated database. A couple Python packages are useful here:

Pandas for data manipulations; SQLAlchemy for interacting with the Postgres instance.

This work is encapsulated in the item pipeline component, NrelScraperPipeline:

open_spider(): called when the spider is opened, this method retrieves our DB credentials from a gitignored dotenv file and configures an engine to establish a connection with said Postgres instance.process_item(): called for every item yielded by the spider, this method reads the raw text data into a Pandas dataframe, before cleaning it up and writing it to the desired table in our database.close_spider(): called when the spider is closed to dispose of all connection resources being used by the SQLAlchemy engine.

As you'll notice, the spider itself is operating in tandem with the process_item()

method. To activate this pipeline, the class must be added to the scraper's settings

and assigned an integer value that determines the order in which it runs (if there

were other activated pipelines too).

# ./nrel_scraper/settings.py

ITEM_PIPELINES = {

'nrel_scraper.pipelines.NrelScraperPipeline': 300,

}

Running the Scraper

With that, this ETL process can be manually triggered with scrapy crawl midc

(where 'midc' is the spider's name) to upload live data to Amazon RDS.

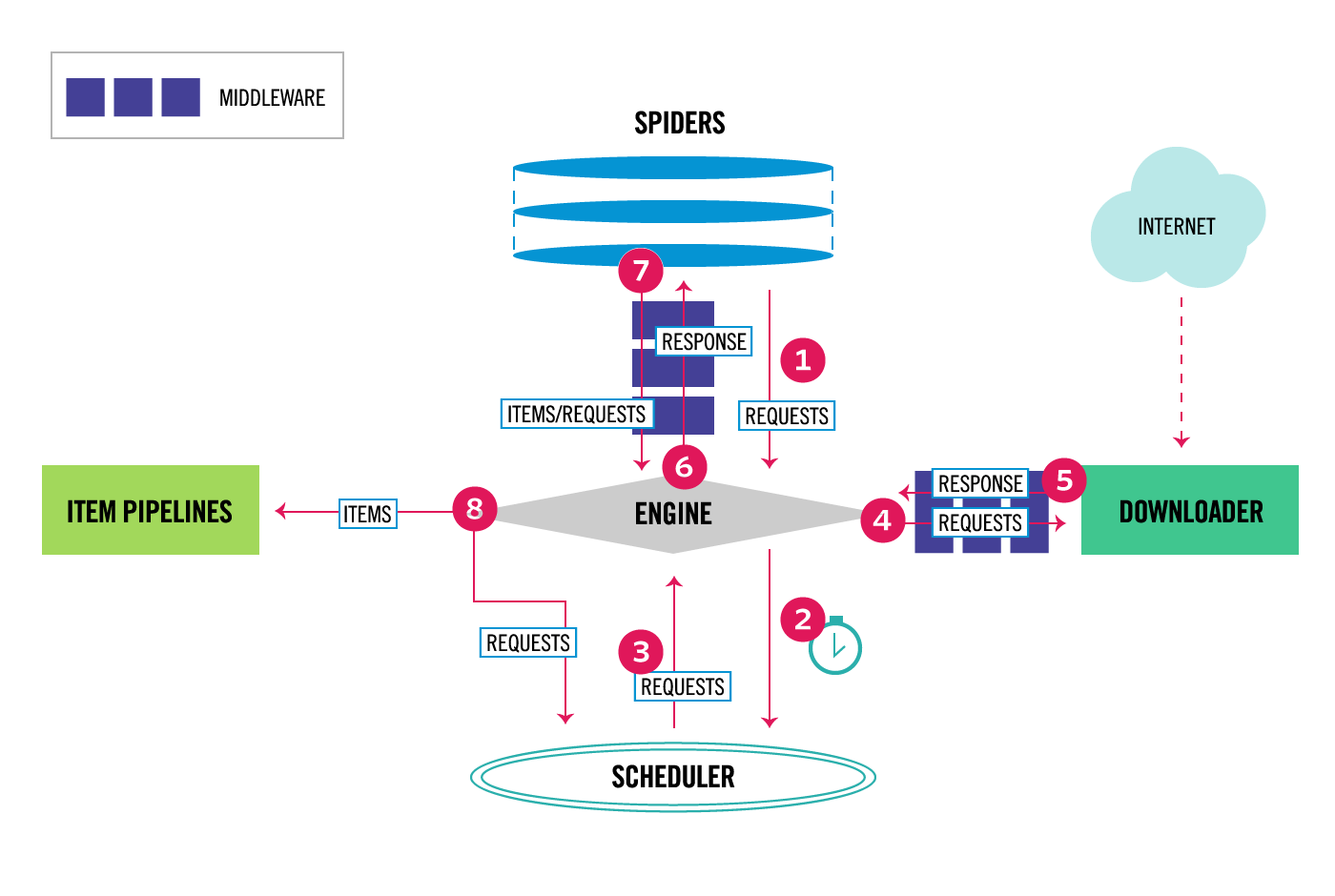

I'd encourage any first-time users to study Scrapy's documentation, where they have some excellent tutorials and provide an overview of the whole architecture.

As things currently stand, I'd have to wake up at 2AM everyday (i.e. midnight in Colorado), run the scrapy crawl for a days-worth of data, and question what I'm doing with my life.

So, next time I'll revisit this topic and discuss how my ETL pipeline can be farmed off to a Lambda function using the Serverless Framework - all on AWS Free Tier!